This is post three of a series, important backstory here.

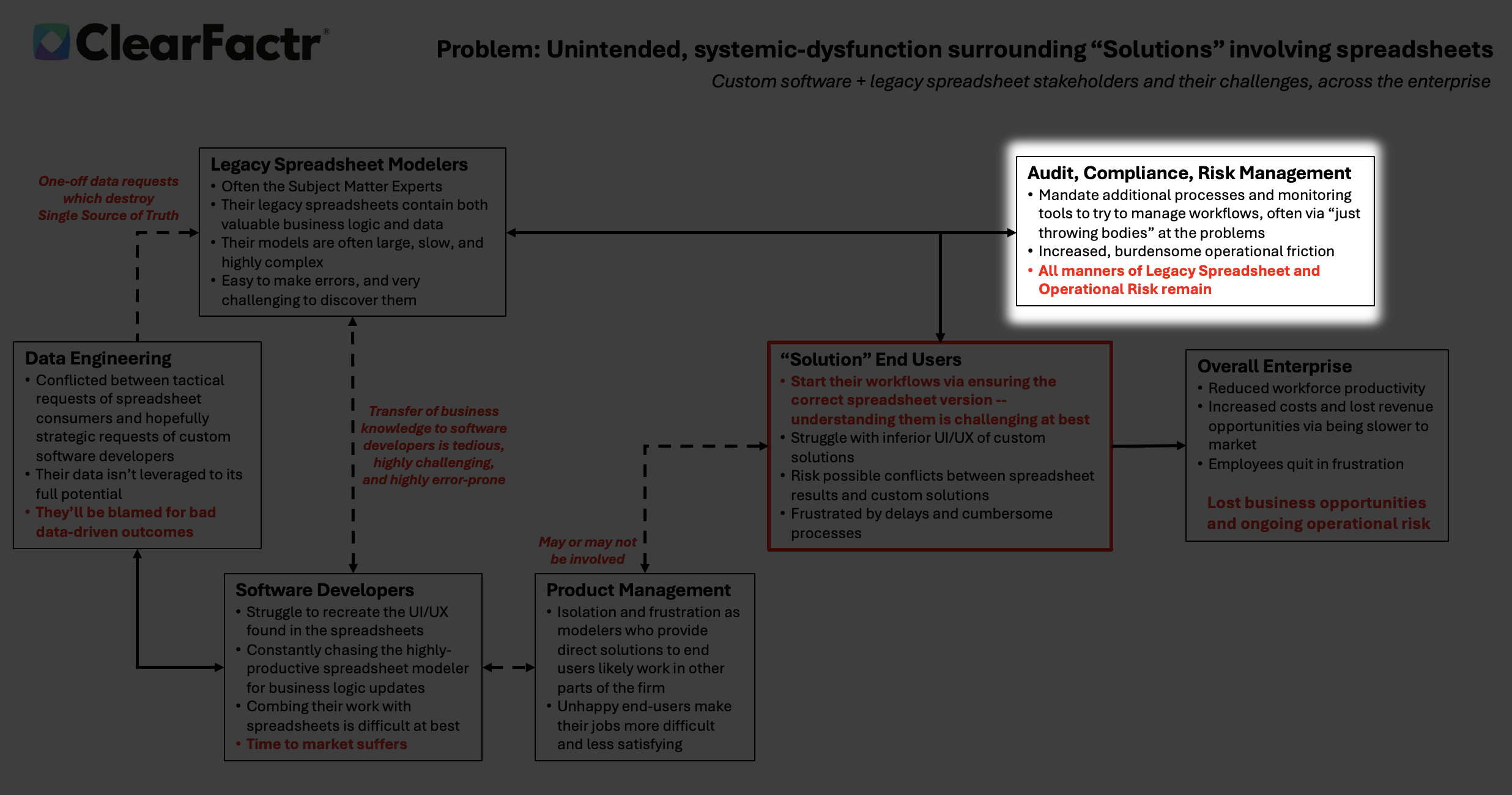

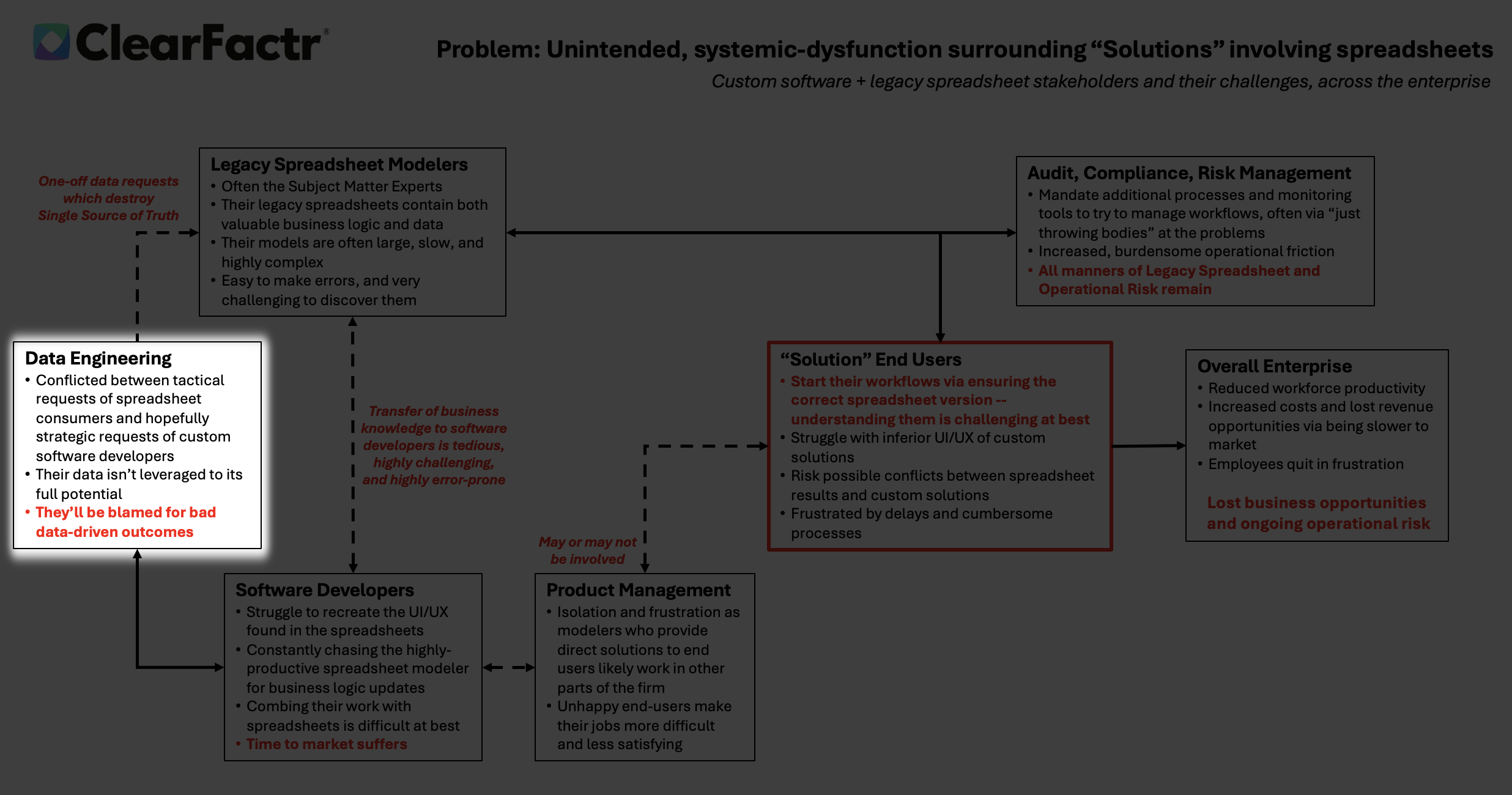

In the heart of many enterprises, a dotted line of friction divides two essential tribes: the Legacy Spreadsheet Modelers, often the unsung subject matter experts wielding Excel like a magic wand, and the Custom Software Developers, architects of scalable, structured systems. This connection, fragile and bidirectional, symbolizes a transfer of business knowledge that's tedious, error-prone, and riddled with misunderstandings. It's like handing off a novel written in hieroglyphs to someone who only reads binary.

What’s the core struggle? Neither group truly speaks the other's language.

Spreadsheet modelers converse in formulas: =VLOOKUP() for finding data, pivot tables for summaries, conditional formatting for insights. All visual, intuitive, and ad-hoc. They build models on the fly, dragging cells to iterate, embedding business logic in sprawling grids that evolve organically.

Developers, meanwhile, think in code: loops in Python or Java, database queries in SQL, object-oriented classes for modularity. Their world is rigorous: functions encapsulated, errors caught by compilers, changes tracked via Git. What a modeler sees as a quick "what-if" scenario, a developer rebuilds as a parameterized API endpoint. This mismatch turns collaboration into translation marathons, where nuances get lost. A hidden assumption in a cell note can easily become an overlooked edge case in code, leading to bugs that surface months later.

Toolsets and workflows amplify the divide.

Excel's strength is its immediacy: no build times, no deployment queues, total control. Modelers can tweak a massive financial forecast in minutes, sharing via email for instant feedback. Developers' arsenals -- IDEs like Visual Studio, CI/CD pipelines, testing frameworks -- prioritize robustness over speed. Integrating the two is a nightmare: exporting CSV from Excel risks data corruption and inevitable data obsolescence; embedding VBA macros clashes with software security protocols. The result: developers constantly chase modelers for updates, combing through opaque sheets to reverse-engineer logic, while modelers resent the "over-engineering" that strips away their tools' simplicity.

End-users, caught in the crossfire, often side with spreadsheets.

They crave the flexibility: self-service adjustments without begging IT for a ticket, independence from the glacial release cycles of custom apps that might take quarters to update. A trader tweaking a pricing model in Excel gets results now, not after sprint reviews and QA. Yet, this autonomy breeds risk. Spreadsheets lack built-in audits, version control, or error-checking beyond basic flags, making them ticking time bombs for operational disasters.

Real-world examples underscore the peril.

-

At JPMorgan Chase in 2012, a spreadsheet error in value-at-risk modeling, stemming from a simple copy-paste mishap that didn't adjust a formula, contributed to the "London Whale" scandal, costing $6.2 billion in trading losses. As someone who's had to translate one-off equity derivative pricing models built in Excel into a C++ position and risk management system, I can attest to the tedium it takes to assure this handoff is done perfectly.

-

Similarly, Fannie Mae's 2003 $1.136 billion equity misstatement arose from "honest mistakes" in an Excel sheet implementing a new accounting standard, exposing the risks when end-users rely on ungoverned flexibility over auditable software.

-

In another case, Barclays' 2008 acquisition of Lehman Brothers assets ballooned unexpectedly when hidden rows in an Excel contract list went unnoticed, forcing them to honor 179 unwanted deals—illustrating how spreadsheet opacity frustrates developers' attempts at clean integration.

Migration attempts reveal deeper tensions. Companies shifting to custom software face cultural resistance: modelers cling to Excel's speed, while developers push for databases to eliminate silos. In IT forums, pros lament "shadow IT" and “End User Computing” where Excel experts build critical apps silently, bypassing developers and creating governance nightmares.

Bottom line outcome: Delayed projects, inflated costs, and persistent spreadsheet risk—until the bridge is rebuilt with better tools.